Melanie Butler grabs a coffee with Xavier Gisbert

“I don’t believe every school should be bilingual. It would be a disaster.” We journalists love people like Xavier Gisbert, mastermind of Spain’s bilingual school revolution: not only is he a master of the pithy quote, but you can never quite predict what he is going to say.

So why, I ask him over a cup of coffee at a recent conference in Estramadura, Spain, would a completely bilingual school system be a disaster?

“Families must have a choice.”

If parental choice has the familiar ring of neoliberalism, that should be no surprise. Gisbert is a long-time member of Spain’s centreright Partido Popular, who left his job as a state school teacher of French to build a career as a civil servant and educational policy wonk, rising to become Director General of Evaluation and Territorial Cooperation at the Ministry of Education and serving as Education Attaché in the Spanish Embassies in both London and Washington DC.

But if he has ended up as a card- carrying member of the elite, he certainly didn’t start as one. Xavier Gisbert da Cruz, to give him his full name, was born in Tangier, Morocco to a Spanish mother and a Portuguese father who both migrated to the country when it was a French Colony. His father died young, and the young Xavier had to fight his way up through Morocco’s Francophone education system, making his way from a top lycée to taking a degree in French Philology at Complutense, Madrid’s most prestigious university.

“You’re a migrant child!” I exclaim.

“Why do you always keep talking about migrant children?”

“Because I was a migrant child and we are the canaries in the coalmine. Migrant children do worse in education generally but we are better at languages. So how do they do when they are at a bilingual school when they don’t have either of the languages?”

“This is not a problem in Madrid,” he sniffs.

He’s right about that. A major research study on student outcomes in Madrid’s bilingual school system, undertaken by the British Council in 2017, found that in a sample of nearly 2,000 state school students, 15 per cent

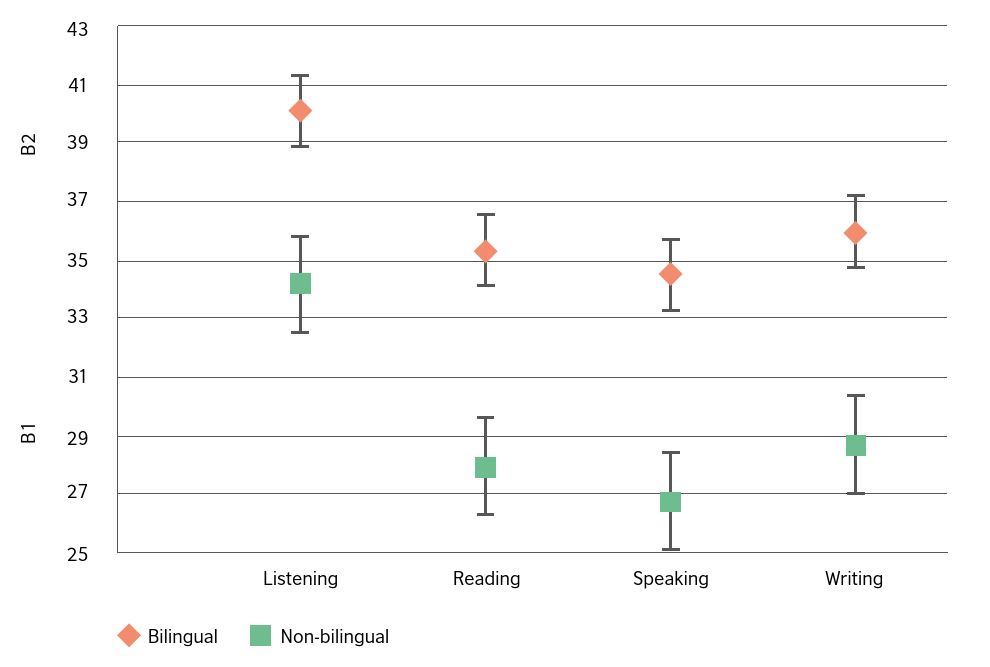

The results of Madrid’s bilingual project

The results, shown in the table at left, are reported across all four skills for both bilingual and non-bilingual schools. On average, students in bilingual schools tested at B2 and C1 level.

were from immigrant families but most were from Latin America. Only 5 per cent did not speak either Spanish or English at home.

There is very little Xavier Gisbert doesn’t know about Madrid state schools. Madrid is where, while working as Director General for Quality Improvement of Teaching for the regional government, he came across a handful of experimental bilingual schools, part of a British Council project.

“They were struggling,” he concedes, “but I thought bilingual could be a very interesting possibility. So I cleared my desk, and I took a large piece of paper and I began to sketch out a plan.”

The plan became the Madrid bilingual school project, a project which by 2017 had revolutionized the level of English in Madrid’s state schools. At age 16, nearly 60 per cent of children in the programme test at B2 or above with, 27 per cent reaching C1 or above, according to British Council research.

The figures are even higher in the elite bilingual sections, the special secondary school programme for children who test well in their L2 at the end of their bilingual primary. The British Council found that 85 per cent of them were at B2 or above, the kind of result you would only expect to see in Sweden or the Netherlands, the best performing English language learners in the world.

Now, the whole bilingual school project is contentious in Spain. The bilingual sections are a major political hot potato, with parties on the left labelling it as selective.

Selective education is not allowed under Spanish law.

“We do not select children. We find the children who have become bilingual and we invite them to join the section.”

I’ve give up arguing with Xavier Gisbert about these things. His opinions are strong and, when the evidence comes in, it tends to support him. I remember, a couple of years ago, asking him whether bilingual schools disadvantaged students with low Socio- Economic Status, or SES.

“Children with low SES always do worse,” he snapped back. “The question is can we reduce the gap?”

And reduce it they have. The L2 levels of low SES children in Madrid’s bilingual schools is lower than that of their more affluent peers, but the difference is significantly wider in the nonbilingual schools, the British Council found. In fact, low SES children in bilingual schools were at the same language level as middle-class children in nonbilingual education. Not what the centre left politicians in the current Spanish government probably want to hear. Perhaps they hope Xavier Gisbert is no longer there to answer back. But though he has left the Madrid bilingual project, the warrior has not left the field. He has set up an accreditation scheme for bilingual schools across Spain, working with language consultancy NewLink.

And what is the single most important piece of advice he gives the schools he is looking to accredit?

“Your teachers must be C1 in the language, or your school will not be a bilingual school.” It’s the Gisbert mantra.

“And why do teachers need to be C1?”

“Because the language of the student…” he starts.

“will never be better than the teacher’s” I finish.

We laugh. All migrant children know that. All language teachers, too. He drains his coffee and stands up to leave. But I have one more question. He is the migrant child who climbed the greasy pole of education, but why did he never become a politician?”

He shrugs and smiles. “Because I always say what I think.”

■ Xavier Gisbert da Cruz has a degree in French Philology from the Complutense University of Madrid. He has been Education Counselor at the Embassy of Spain in London, Director of the Regional Center of Innovation and Training “Las Acacias”, Director General of Improvement of the Quality of Education of the Ministry of Education of the Community of Madrid, General Director of Evaluation and Territorial Cooperation in the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport and Education Counselor of the Embassy of Spain in Washington. He was a promoter of the International Congresses of Bilingual Teaching (CIEB). He is the author of several publications and is currently President of the Bilingual Teaching Association (EB).