A look at team teaching within the Hands Up Project’s online sessions

The Hands Up Project is a UK- registered educational charity, providing online learning for young people, mostly in Palestine, through conversation, storytelling and drama. Team teaching – with at least one teacher from the community of the learners and at least one other connecting from another country – has been an important feature of what it does.

Experienced teachers know that if we want to help learners develop their speaking skills,

we need to be as good at listening as we are at speaking. We also need to be able to listen in two ways. First, to hear what learners are saying and, second, we need to listen to how they are saying it, to know if they are improving and find ways to support their spoken language.

A pre-Covid 19 example

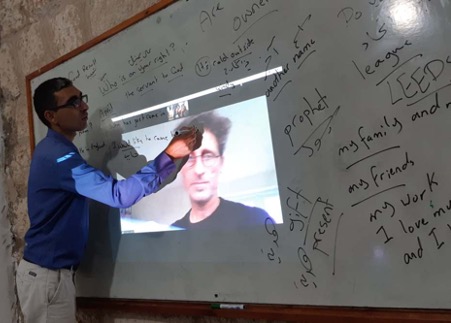

The picture (right) shows a typical team-taught Hands Up Project session before the corona pandemic. Atiyyeh is an English teacher

“A classroom teacher and a remote volunteer working in unison can be very rich in language-learning opportunities”

in a village close to Ramallah in Occupied Palestine. He’s running an after-school English class for a group of 14- to 15-year-old boys.

Michael is an actor and professional storyteller, and he’s connecting through Zoom to Atiyyeh’s class from his home in Bristol in the UK. Michael is talking to the boys, listening to what they’re saying and chatting with them. The boys are generally taking it in turns to come up to the laptop and interact directly with Michael while the others listen. Occasionally Atiyyeh will ask Michael to pause, so that he can focus on some of the language that Michael’s used or set up a drill or practice activity. He might ask Michael to repeat words that he’s used or provide other examples. As the teacher, Atiyyeh is in charge of the pacing of the discourse, and making it accessible and useful to the learners. Michael’s responsibility is to keep the conversation going. Both roles are important, and together they provide a pedagogical and social aspect to the conversation.

These types of conversations, where you have a classroom teacher and a remote volunteer working in unison, can be very rich in language-learning opportunities. Below is a transcript of such a conversation. Ahmed is a 15-year-old boy in Palestine and he’s been asked to talk with the remote volunteer about his home. Notice how the support provided by the remote volunteer and the classroom teacher provides a scaffold in which the student can experiment with vocabulary, and the meaning and form of the present perfect versus present continuous tense.

Ahmed: In the village we have another home in the village is away from the home we are living in. He’s to my brother and my dad he’s build the a home up our home. [The classroom teacher provides him with ‘second floor’. ] A second floor.

Remote volunteer: Aha.

Ahmed: For me.

Remote volunteer: Your dad – did you say he has built it or he’s building it? He has built it?

Ahmed: He’s a builder.

Remote volunteer: No, but did you say he has built it or he is building it?

Ahmed: He is building for me a home for me. Remote volunteer: He’s building it now? When will it be finished?

Ahmed: Next year on the summer.

A post-Covid-19 example

In March 2020, as Covid-19 struck in the West Bank, schools all over Palestine were closed until July. We couldn’t do any of the things that we’d been doing and would have to completely reinvent ourselves. We did this by moving all our operations to Facebook Live. This meant that we could no longer see or hear the participating children and the only way they could engage was through writing comments. On the other hand, there were also certain advantages to this way of working.

Advantages of doing sessions on Facebook Live

- Students can access the sessions from their own homes, using weaker internet than is required for Zoom, and just a mobile phone if they don’t have a laptop.

- A far greater number of students could access sessions. Some of our Facebook ones have had thousands of views.

- Students can potentially get support from family members with English or the technical aspects of accessing the sessions. In some situations, where children have a higher level of English, and/or more advanced technical skills than their family, this support process may work in the opposite direction.

- Since all the recordings are stored on the Hands Up Project’s Facebook page (see examples at https://www.facebook.com/ watch/handsupproject/), students can re-watch sessions for extra practice or watch them when it’s convenient.

- Students can write comments as a way to practise and develop their written English skills.

- There are many teachers from different countries present in the sessions who can provide the kind of scaffolding outlined above to the learners’ comments. It also serves as a teacher- development tool, as teachers see other ways of working and may get new ideas for their classes.

- Since the sessions are free and open to anyone, there are opportunities for learners in Palestine to meet and interact with other learners of English around the world.

We didn’t lose anything in terms of the benefits of team teaching. In fact, there was another kind of team teaching going on, where one teacher was delivering the session, and others who were watching were responding, clarifying and scaffolding what was written in the comments.

During the second lockdown, which began in August 2020, we introduced team-taught, curriculum-based Facebook Live sessions. For these, we went live on Facebook through Zoom, so the two teachers could be visible and audible to the participants. For each grade we had one Palestinian teacher working in tandem with an English teacher from another location in the world. Typically, the two teachers would focus on areas of language from the course book English for Palestine. They might propose personalised practice activities for the students to take part in the comments and they might talk to each other, perhaps demonstrating the activity.

These conversations between the teachers provide excellent models for the learners, but also expose them to natural conversational English, something which is often lacking in standard classrooms.

In one of these sessions, lead by Sahar Siam from Gaza and Lauren Edmondson from Australia (see screen shots, opposite page; facebook.com/917350095017969/ videos/815479105930117), the two teachers discuss their hobbies as a way to review the present simple tense. They then invite the students to write what their own hobbies are in the comments. Notice that the same type of scaffolded interaction discussed earlier is taking place in the comments, albeit written rather than spoken.

What the local teacher can bring to the table

- In-depth knowledge of the curriculum (thereby more easily catering towards success in local exams).

- Knowledge of classroom practices which learners in Palestine are familiar with. 3) Knowledge of both Arabic, the L1 of the

- learners, and English.

- Knowledge of the learners’ personalities,

- their strengths and their weaknesses.

- Local cultural knowledge.

What the foreign teacher can bring to the table

- Knowledge of classroom practices which may be new and motivating for learners.

- A motivating stimulus for the learners to use English, due to a lack of L1.

- A source of exposure to more international/non-Palestinian forms of English.

- A reason for the local teacher to use natural spoken English.

- Sharing inter-cultural knowledge.

Nick Bilbrough is a teacher, teacher-trainer and author. He holds an MA in Drama in Education, and is particularly interested in the role of drama and storytelling techniques in second-language learning. He is the author of two books in the Cambridge Handbooks for Language Teachers series: Dialogue Activities (2007) and Memory Activities for Language Learning(2011), and wrote Stories Alive, published by the British Council, Palestine. He now devotes all his energy to the registered charity he set up, handsupproject.org.