Melanie Butler predicts the effect of the new tests

The plan to introduce, in the OECD’s 2024 Pisa tests, an optional foreign language assessment, will increase the pressure on school systems around the world to improve the level of English of their under-16s.

Many governments set huge store on their countries’ Pisa results. Rumour has it, for example, that Poland reduced its emphasis on English to increase classroom time dedicated to the three subjects currently tested: maths, science and reading.

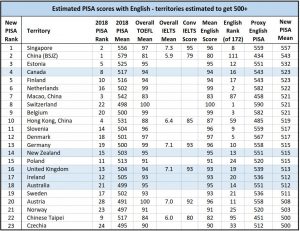

Whatever Poland did to improve its Pisa scores, it worked. If you look at the Pisa 2018 table below, which ranks countries based on the mean average of all three subjects, Poland ranks number 11, just below Finland.

Now, the OECD disapproves of averaging the scores across the subjects, but national governments and, of course, the media do it anyway. So, could the introduction of optional English tests turn the Pisa tables upside down?

As part of the media, and as a magazine which does its share of ranking, EL Gazette decided to see what would happen if we added English scores into the mix. We used a combination of national average Toefl scores and, where available, Ielts scores by country and used the marking base and score distribution system used by the OECD to come up with a proxy Pisa-style English score.

Of course, the population of students taking the Pisa tests are a demographically representative sample of 15-year-olds in each territory, whereas candidates for Ielts and Toefl (whose scores correlated extremely closely) are largely drawn from super-bright and often super-rich 18-24-year-olds. The results, however, do generally seem to match the one international test for 15-year-olds we do have: the EU tests designed by Cambridge which were piloted in 17 European countries in 2012.

We also included the English scores for the majority English-speaking countries which, you will notice, are not the highest. In the case of Toefl, that may be partly because the score is the average of everyone who took the

“Could the introduction of optional English tests turn the Pisa tables upside down?”

test in that country, so will include international students. Ielts scores for a country are based on nationality, but for the one English-speaking country where we do have results from both tests the correlation between them is very close.

So, what is the impact of adding in English?

Well, it’s bad news for East Asia. In the Pisa 2018 ranking, 6 of the top ten ranking countries come from the region, or 7 if you count Singapore, which is in South East Asia.

Singapore comes top when we add in English scores, though China maintains second place, despite ranking 111 for English! Only two other East Asian territories, Hong Kong and Macau, stay in the top ten while Taiwan drops to number 22 and Japan and Korea don’t even make our ranking.

Meanwhile, Northern Europe leads the rush up the ranking, with Eastern and Central Europe close behind. Southern Europe still doesn’t get a look in – the English test scores for Latin language countries, though higher than those from Asia, are significantly lower than for the rest of Europe and not enough – when averaged with their scores in the other Pisa subjects – to push them to the top tier.

In terms of language learning, the results closely mirror those from the EU tests in 2012 where the speakers of Germanic languages, like Dutch and Swedish, had the highest scores, with the Slavic language speakers a little behind on average and the Latin speakers following on behind.

This fits in with the language distance hypothesis which posits that it is easier to learn a closely related language, as Dutch is to English, then a more distantly related one, like Spanish. Hardest of all is learning a completely unrelated language like Dutch compared to Arabic.

Indeed, as we reported last issue, in a sample of 50,000 migrants learning Dutch, language difference was key – with only the best 5 per cent for L1 Arabic-speakers doing better than the bottom 50 per cent of Germans.

However, this does not explain the excellent results of Estonia – not only on Toefl, but also in the EU 2012 test. Estonian and Finnish are Uralic languages which are not Indo-European.

However, both of them are multilingual countries: a quarter of Estonians speak Russian, while all Finnish school children spend four years learning the language of their main minority, Swedish. The top Asian country for English is Singapore and the highest English score overall came from Switzerland and with Belgium, Macao and Hong Kong all ranking highly, multilingual territories may have the advantage.