Melanie Butler speaks to one of the owners of a language school that has transformed people’s lives

‘CLAC has changed my life. I don’t do what I do for money. I do it because I love it.’

For double Bafta-winning documentary maker Oggi Tomic, these words are not empty rhetoric.

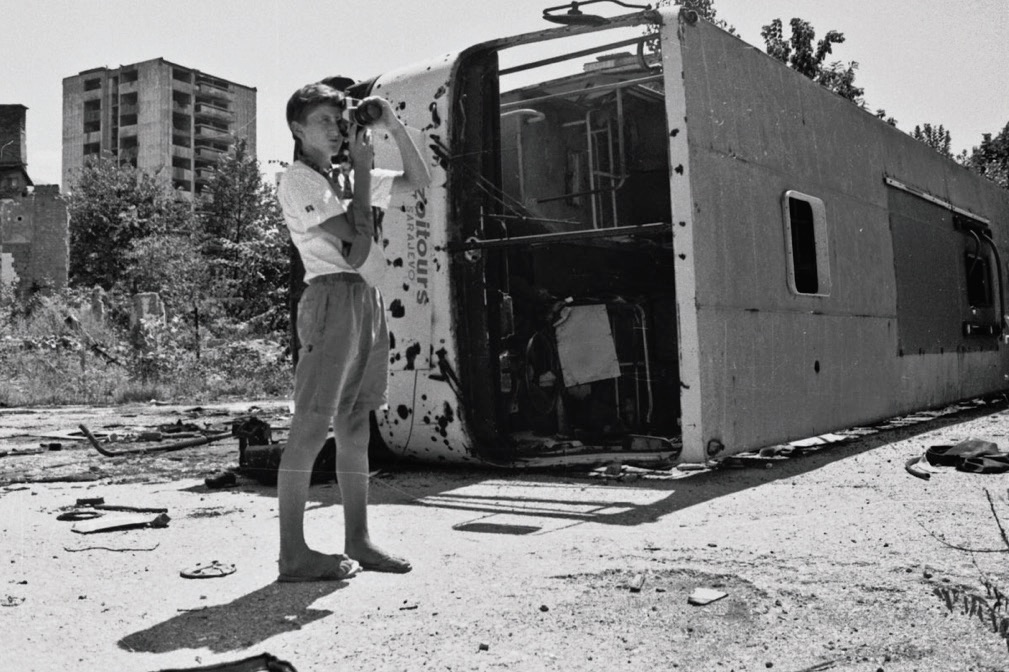

Oggi arrived at Cambridge Language and Activity Course (CLAC) eighteen years ago on a scholarship, and this exclusive family-run English language summer school really transformed the Bosnian orphan’s life. Forever.

But things did not go well straight away.

‘I took one look at it. Big building, full of children – I thought that was just like another orphanage. I had been to five. My friend and I decided to rebel,’ Oggi tells me down the phone. The rebellion lasted precisely 24 hours. On the second morning, Anne George, who founded CLAC with Elfrida Heath in 1985, called him into her office.

‘Do you want to be good? Or do you want to leave?’ she asked. Oggi decided to be good. Apart from one time in 2001, he has come back every summer ever since and now works year-round as enrolments manager when he isn’t making films.

Elfrida has retired, but Anne George and her son William still run the summer school, and still follow the traditional CLAC approach, which emphasises ‘personalised attention to the children and their parents’.

‘The very first thing William and I do when we pick children up from the airport,’ says Oggi, ‘is ask them if they are hungry and remind them to call their parents.’ Every parent has a point of contact within CLAC, who send them emails, photos and updates throughout the course.

This is a family business. The mother Anne runs one centre while her son William runs the other. William’s wife, Carolina, teaches yoga to the students and Oggi, the ‘informally’ adopted brother – they never could find his birth mother to make it official – teaches them filmmaking.

‘William taught me when I first came – English through science. I think I remember the Bunsen burners. Was it science, William?’

“Everybody who comes to CLAC once comes back, or so it seems”

The other permanent member of the CLAC team is their general manager, Hazel Pelling, who started work there as an English language teacher in 2009. Nine years later, she’s still there, making sure everything runs smoothly.

Everybody who comes to CLAC once comes back, or so it seems. This year, 80 per cent of the teachers were returners and 70 per cent of the students had also been there before.

‘Last year we had our first second generation student. The mother came and now her child.’ Word of mouth accounts for 20 per cent of enrolments. Then there are families who find them through the web. And agents? Oggi puts down the phone to consult his adoptive brother. ‘William says that about 2 per cent of our students come from agents,’ he reports back.

‘He’d like about 10 per cent from agents, no more than 20. Besides, we can only take small groups.’

Word of mouth is also the way that British children are recruited. Having English-speakers in the mix has always been an essential part of the CLAC experience. In the old days, they were enrolled in foreign language courses, but these days they form part of a buddy system, acting as cultural ambassadors.

‘It works brilliantly,’ Oggi chortles. ‘I still have British friends I met as a student at CLAC.’ Another feature of the CLAC experience is the high ratio of adults to children. They have one adult to every four students and, needless to say, some of those adults are former students.

‘We don’t take students over 17, so they ask if they can come back as helpers,’ Oggi says. ‘We tell them to take a year or two off, see the world. Then back they come.’

CLAC is not just a language school, it seems, it’s a way of life – although the team certainly take the language learning seriously, and not just in the classroom. Children share rooms with someone of another nationality. English is encouraged at all times, screen time is limited and mobiles are taken away at night.

‘You take mobile phones away from teenagers?’ I asked, amazed. ‘Isn’t there a riot?’

Oggi replies, ‘We keep them so busy, they don’t really notice’.

Finally, as a parent who spent years sending children on summer language courses, I ask about end-of-course reports – something I never once received in eight years.

‘Every child gets a report, hand-written by the teacher, with notes from the centre manager and also from a director. And a certificate. Oh and a memory stick with photos from the course.’ Oggi pauses.

‘I still have my report and my certificate from when I first came from Bosnia,’ says the boy who went to a summer school and found a family.