The Gazette editorial team’s selection of ELT news from around the world

JAPAN:

An investigation by Japanese newspaper Mainichi Shimbun reveals that 13 of the country’s 82 national universities will accept applicants to some of their faculties who have English at junior high school level – equivalent to just A1 on the Common CEFR, rather than the ‘mid-high school’ level of A2 recommended in recent government reforms.

Under the new system, to be introduced in academic year 2020, applicants take a standardised entrance exam, to which they can add ‘points’ by taking one of eight approved private English language tests, including Toefl and Eiken.

The 13 institutions accepting lower English language levels include three teacher training colleges and one agricultural university, mostly in regions with “regional and economic disparities.” The lack of local test centres for private English language tests were a factor in the decision to lower language requirements.

MEXICO:

An expansion of English-language teaching in state education is expected following a Senate vote in May passing an amendment to Mexico’s constitution. The amendment strengthens citizen’s rights to language learning.

The Christian Science Monitor reports that the amendment imposes greater standards of accountability on the federal government, and clarifies what citizens should have access to in terms of language learning. This means those going to court to ensure their access to language learning will have greater power, with the right to language learning more easily enforceable.

Designed primarily to ensure that Mexico’s indigenous groups have greater access to learning in their own languages, the constitutional amendment is likely to result in court actions aimed at securing the provision of English language classes throughout Mexico.

While most leading public sector universities have an English language requirement for entry, around 70 per cent of Mexico’s primary school students have no access to English classes at all.

SWEDEN:

A motion put before the municipal council of Skurup, in the south of Sweden, proposes banning the speaking of any language except Swedish in schools, even during breaks. The motion, brought in June by a group of councillors from right-wing nationalist party Sweden Democrats, states that “it should be Swedish that is normally used as a language of conversation in corridors and classrooms, for a faster integration into Swedish society.”

The country’s tradition of taking in refugees means there are many bilingual students in Sweden. Arabic overtook Finnish as the second most-widely spoken language in 2018, following the arrival of large numbers of Syrians. Recent arrivals often communicate using English as a lingua franca, a practise which would also be covered by the ban.

According to Daily Sweden, the motion grants exceptions for the official languages of Finnish and Sami (a Lapp language,) and to “official minority languages,” which include Meänkieli, Yiddish and Romani. “Regular language lessons” featuring foreign languages – presumably including English – would still be permitted.

CHINA:

Three Chinese recruitment agents have been sentenced to one to year in prison for bringing foreign kindergarten teachers

into the country without the right qualifications or work visas, according website Globalnews.cn.

The agents, who were charged with, “organising people to secretly cross the national boundary,” were also fined 10,000 yuan each.

As we report on page 6, the recent crackdown on English language teachers without the right qualifications and experience has led to an increase in the number of teachers being arrested and deported. This is the first case we have come across where authorities have focussed on recruitment agents, many of whom claim falsely that teachers can work on a tourist visa.

MALAYSIA:

The president of Malaysia’s biggest teacher’s union, the National Union of the Teaching Profession, has called on the Education Ministry to conduct a “comprehensive study… to determine the cause [of the] decline” in English proficiency nationally.

Speaking at a seminar for English teachers in May, Aminuddin Awang cited a shortage of English teachers, along with a lack of motivation from students, as a pass in English is not required for Malaysian Certificate of Education exams.

Awang was responding to an Education Ministry directive stating that English teachers will have to take the Malaysia University English Test (MUET) as part of school reforms requiring English teachers to achieve C1 on the CEFR.

The Education Ministry has since launched a campaign to recruit more English teachers and to induce former English teachers to come out of retirement.

MONGOLIA:

A former English language teacher in Mongolia has won the world’s biggest environmental award for her work protecting snow leopards.

Bayarajargal Agvaantseren worked as teacher and translator of English and Russian, graduating in the early 1990s and interpreting for US Peace Corps volunteers.

It was in her capacity as a translator for scientists for the Snow Leopard Trust in 1997 that Agvaantseren encountered the critically endangered snow leopards in the Southern Gobi Desert. This inspired her to set up an insurance scheme for shepherds who lost their animals to snow leopard predation. She became the director of the Snow Leopard Trust, lobbying for the creation of the Tost Tosonbubma nature reserve.

Starting in 2009, she mobilised local nomads to oppose mining interests that were destroying snow leopard habitats. Thirty-seven mining licences in the region were cancelled after her campaign caused parliament to declare a State Protected Area.

In April, Agvaantseren won the Goldman Environmental Prize Asia, including $200,000 to help recipients “pursue their vision of a renewed and protected environment.”

HONG KONG:

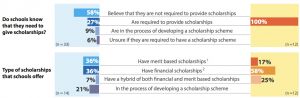

Private English-medium schools in Hong Kong are often unaware of their obligations to set aside some of their profits for scholarships for poorer students, a report from the education think-tank the Zubin Foundation has found.

Private schools are required by law to set aside a tenth of their profits for scholarships for disadvantaged children, in return for free land provided by the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

A Zubin Foundation report entitled Missed Opportunities for English Language Education for Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong, found that 58 per cent of foundations surveyed didn’t believe they had any scholarship requirement.

The report argues the money could be used to fund education for the Special Autonomous Region’s English-speaking ethnic minority children.

It notes that many ethnic minority children, particularly Pakistanis and Nepalis, struggle to master Cantonese and would benefit from “an excellent education in English,” in which they are proficient rather than the “poor education in Chinese” they often get.