Stimulating the vagus nerve may help perception of pitch, study shows

Stimulating the vagus nerve via the outer ear could improve listening skills in language learners, according to research from the Universities of Pittsburgh and California San Francisco.

Recognising and learning the new sounds of a second language requires the same mental processes an infant uses to learn their first language: attention, accurate perception of the sounds and commitment to memory. Sounds simple, but adults often struggle with all three – and not just in language learning.

As the brain matures it tends to become less flexible in learning – less plastic. While infants apparently distinguish easily between the sounds of different languages, over time the brain sacrifices this plasticity to focus on recognising the characteristic sounds of its native language – the

one it will depend on every day. This is why adults find some sounds in foreign languages especially difficult to recognise and reproduce.

One famously difficult example of this occurs when adult English speakers attempt to learn Mandarin Chinese. Among the tricky sounds for English speakers is the use of tones in Mandarin that change the meaning of words but have no equivalent in English.

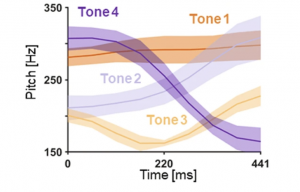

There are four such tones, differentiated by changes in pitch:

- Tone 1: a sustained high pitch

- Tone 2: starts low then rises

- Tone 3: starts low, dips lower than rises but is never high

- Tone 4: starts high then falls low

Studies have shown that English speakers are better at hearing the average pitch than the change in pitch, so find the difference between tones 1 and 3 easier to recognise than between tones 2 and 4. This enabled the researchers to create two blocks of tasks, one easier and one harder.

An intervention group of 36 English speakers were trained for 25 minutes by listening to tones, identifying which tone was used and then being given corrective feedback. After the training, their learning was assessed with a new bank of examples given without corrective feedback.

During training the intervention group wore an earbud that delivered a small electrical pulse, imperceptible to the wearer, to a point on the outer ear. This pulse stimulates the vagus nerve, one of the major nerves with many functions throughout the brain and body. The study also recruited control groups that were neither stimulated or trained.

Stimulating the vagus nerve is increasingly used to treat a range of conditions, such as epilepsy and severe drug-resistant depression. In these cases, stimulation is applied by a device inside the chest and has a number of safety issues. The transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation, or tVNS, used in this study, by contrast, is easy to use and non-invasive.

Learners who wore earbuds supplying tVNS significantly outperformed controls on the easier contrasts, but not the harder contrasts. During the six blocks of training tasks, learners with tVNS were as competent by block 3 as controls after all six blocks – a 26 per cent increase in learning speed.

After training, learners that had the tVNS also showed better retention of their learning when tested – but again, only for the easier contrasts. It remains to be seen whether learning harder tasks can be improved with extended use of tVNS and training, or whether the effects are restricted in some way.

Researchers were able to test whether the improvements were simply due to improved sensory perception, i.e. whether they could just hear the different tones more clearly, but that explanation was ruled out.

It seems that by stimulating the vagus nerve directly, activity in several brain regions is enhanced, so that attention is primed to receive the sensory input – the sounds. If so, then this technique has the potential to improve many kinds of learning

The authors connect these findings to the ‘Social Gating Hypothesis’ of language acquisition – the proposal that social interaction produces the increased arousal and attention in the infant brain necessary to process language. In that sense, tVNS may succeed by returning the adult brain to a sense of infantile excitement.

REFERENCE

- Ilanos, F., McHaney, J. R., Schuerman, W. L., Yi, H. G., Leonard, M. K. and Chandrasekaran, B. (2020) Non- invasive peripheral nerve stimulation selectively enhances speech category learning in adults, npj Science of Learning 5: 12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0070-0