Ninety years ago, a Danish academic wrote: “It is important to keep the two concepts time and tense strictly apart”. Unfortunately the writer was Otto Jespersen. I say unfortunately because although Jespersen wrote this in chapter 23 of his Essentials of English Grammar, arguably the most substantial and important English grammar of the first half of the twentieth century; it was advice whose unintended effects have shackled the teaching of grammar – as opposed to linguistics – ever since.

Admittedly, the teaching and study of grammar were already in the doldrums in 1933, as Hudson and Walmsley demonstrate in The English Patient (2004). Long before Jespersen, British academics had sidelined the study of the contemporary language as being of minor interest compared to the more noble study of literature.

Jespersen’s separation of time and tense led to the premise that there are only two tenses in English, a concept that has flummoxed generations of students and language teachers. Separating time and tense may have been a quantum leap for research in linguistics, but as a tool for explaining language use, it rather complicated life. Grammar and linguistics (should) have neither the same approach nor the same purpose, yet the twentieth century’s academic infatuation with linguistics has left the two intimately wedded.

It has not been a happy marriage, and it is high time now for a divorce. The marriage was one of convenience; a century ago, grammar was a well-established and noble family, with a pedigree stretching back to Ancient Greek and Latin. English grammar was born in the sixteenth century with strong Latin genes, genes which remained prevalent right through to the twentieth century, by which time the subject was desperately in need of new blood. Linguistics brought into the world by Ferdinand de Saussure, was a natural suitor.

The marriage was a convenience for both parties, English grammar was a field of philology in decline and linguistics was a bold new human science in search of a place at the academic high table. It was a fruitful marriage too, giving birth to a large family including Generative Grammar, Transformational Grammar and others, most sporting the surname Grammar, but adopting the two-tier approach to language derived from Saussurian Linguistics.

Jespersen’s separation of time and tense was part of that two-tier approach. For Jespersen, time was “independent of language”, whereas tense was “the linguistic expression of time relations”; the problem with this is that no one who thinks about language for any reason other than linguistic analysis thinks in terms of a two-tiered approach. Humans intuitively associate notions of tense and time, and indeed in many languages such as French, tense and time are the same word.

Jespersen was not the first to claim that English had only two tenses. Way back in 1726, Priestley, in The Rudiments of English Grammar, had come to this conclusion, though later contradicted himself by referring (p23) to other tenses which he called compound tenses… and in so doing underlined the predicament that faces grammarians when trying to separate time and tense. In the history of books on the subject, the lack of agreement over the number of tenses in English is astonishing.

In 1973 Quirk and Greenbaum published their seminal University Grammar of English, from which all subsequent major grammars take their cue. From Quirk onwards, linguistics was definitely the dominant partner in the marriage; and although the great handbooks of the English language published since the 1970’s have used the family name Grammar in their titles, their authors have mostly been professors or researchers in linguistics, approaching grammar in the Saussurian tradition. One may speculate as to what impact Quirk’s magnum opus would have had, and the sales it would have generated, had its title been A University handbook of English Linguistics.

As Hudson observed in the English Patient, “the overwhelming majority of linguists simply do not see any link between their research and school-level education.” This begs the question “Why not?” The simple answer is that the terms Linguistics and Grammar have been wilfully confused for over half a century. It is time to end this confusion, and reserve one to refer to a field of academic research, and the other to the art of describing how language is used.

While lamentations about the poor grammar skills of students are not limited to English-speaking countries, the lack of grammatical awareness seems particularly acute in the English-speaking world. I remember running a translation course with third-year language undergraduates from top UK universities, when a young man told me how eye-opening it was to “do some grammar”. It transpired that none of the students had ever had any instruction in the subject

In the English-speaking countries, among the reasons for the decline in grammar skills is the fact that for much of the past sixty years, the subject was largely or entirely excluded from school curricula. Though this has now changed, the damage is done, leaving large numbers of English teachers in schools and language centres who themselves have had little or no training in the subject . Those who had most training are teachers whose degrees involved a course or module in linguistics or grammar where in most cases the approach was morphosyntactical, in line with linguistic orthodoxy, and thus ill-suited to the needs of teaching .

The issue of grammar teaching has been under the spotlight in the UK for at least forty years, but without reaching any consensual conclusion, and apparently without achieving any great results. In How grammar is taught in England should change (sic) (2022), Dominic Wyse, professor of education at UCL, concluded that “a review of the requirements for grammar in England’s national curriculum is needed”. Wyse cited the results of an experiment involving primary school pupils some of whom were taught with a new approach “us(ing) modern linguistics to teach grammar”. But, he continued, “the test results of the experimental trial did not find an improvement in the pupils’ narrative writing as a result of the grammar intervention.”

Could this lack of improvement be due, at least in part, to reluctance to throw off the straitjacket of “modern linguistics”? When decades of attempts to improve grammar teaching with its help seem to have provided few tangible results, maybe it’s time to change tack. Of course it takes courage to go against the grain of orthodoxy and say,

“Let’s forget about modern linguistics and approach grammar teaching in a different and independent way.”

The teacher or researcher who adopts this approach will come up against plenty of resistance; but unless new approaches are tried, then there can be no proof that they do not succeed. Grammar existed before linguistics, and while it would be fatuous to advocate a return to “traditional grammar”, divorcing the two would be a good start for any new experiments.

It is worth noting here that the grammar teaching problem is particularly acute in the sphere of teaching English as a first language. In EFL / ESL, where teachers and coursebook writers have not been subjected to the constraints of a specific national curriculum, approaches have remained more varied and more rooted in tradition.

Evidently no divorce between will be total. Linguistics has thrown great light onto the way language functions, and much of this can help better explain how languages are used; but the baseline of modern linguistics, the Saussurian two-tier division, has not helped to make grammar more understandable for students, nor even for teachers who have not studied linguistics. Until this is recognised, attempts to reform the teaching of grammar “us(ing) modern linguistics” may be like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Divorced from linguistics, grammar can be explained in a way that is much more understandable to lay readers. There is no need for technical jargon, just for essential terminology, little need for morphosyntaxic analysis, just for semantics and of appropriate examples. If post-linguistic grammar were to have three keywords, they would be clarity, simplicity and relevance.

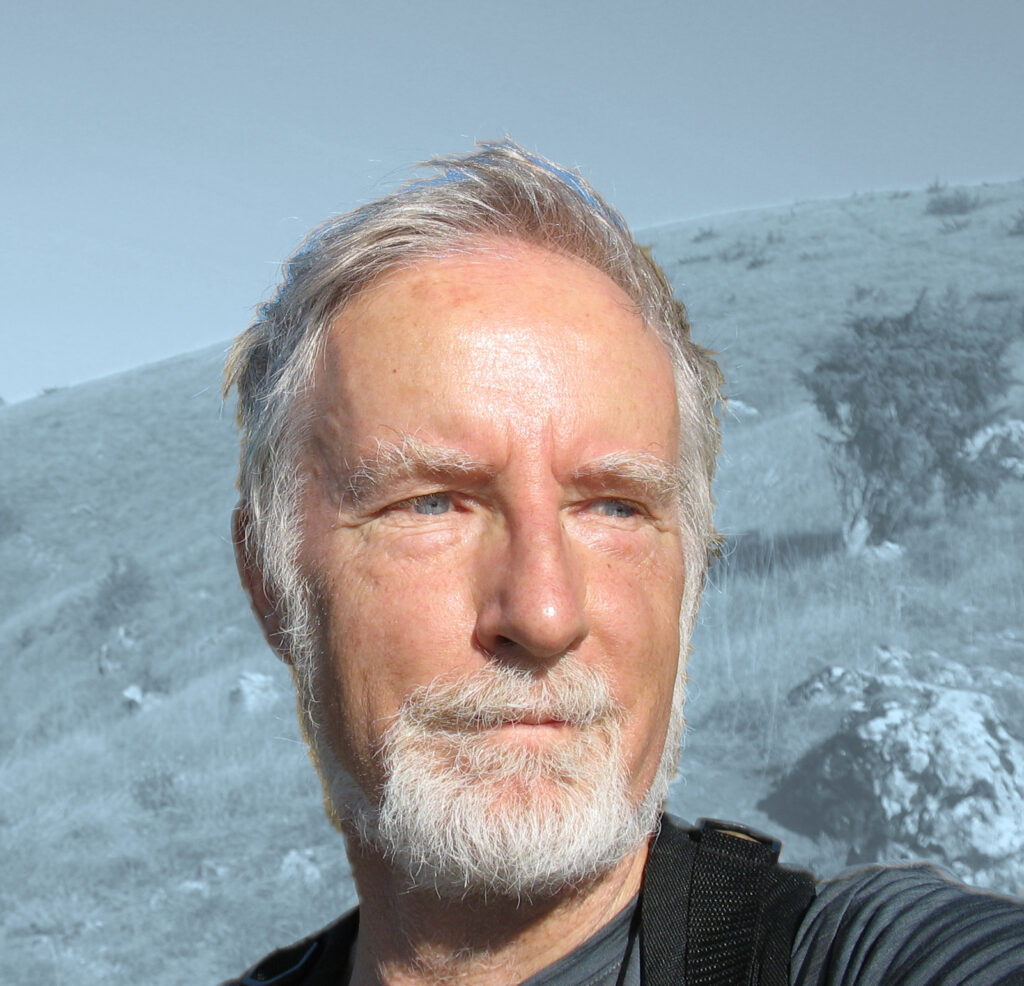

Andrew Rossiter, former head of Applied Languages at the University of Besançon – Franche-Comté in France, is the author of A Descriptive Grammar of English (2020).

Bibliography:

Hudson, Richard and Walmsley, John, 2004. The English Patient.

Jespersen, Otto. (Alan and Unwin, 1933). The essentials of English Grammar.

Priestley, Joseph, (1726). The Rudiments of English Grammar.

Wyse, Dominic (2022) “How grammar is taught in England should change.” in The Conversation, April 2022.