European universities are rushing to offer degrees in English, but which countries are embracing them the most? asks Claudia Civinini

Bachelor’s degrees taught in English are booming across Europe, growing fifty-fold since 2009, a report from StudyPortals and the European Association for International Education has found. The study drew on the database of English-taught programmes listed on StudyPortal’s website to paint a picture of Europe’s internationalisation efforts.

It also included interviews with programme coordinators and national agencies to add insight into the figures. The boom in undergraduate degrees taught in English follows the trend initiated by the Bologna Process, which aimed to harmonise higher education across Europe. The Process has a focus on multilingualism but the boom in English-medium programmes is an unintended, but foreseeable, consequence.

But how are English-medium bachelor’s courses changing the landscape of European higher education institutions? What are the challenges ahead? Here is a round-up of the main findings of the study.

A new normal

English-taught bachelor’s (ETBs) were relatively uncommon in 2009, when only 55 such courses were registered on StudyPortals’ platform. This year, there were almost 3000.

The growth of such programmes follows the lead of the popularity of English-taught masters degrees. Generally, the study reports, institutions introduce their masters programme first. However, there are some exceptions.

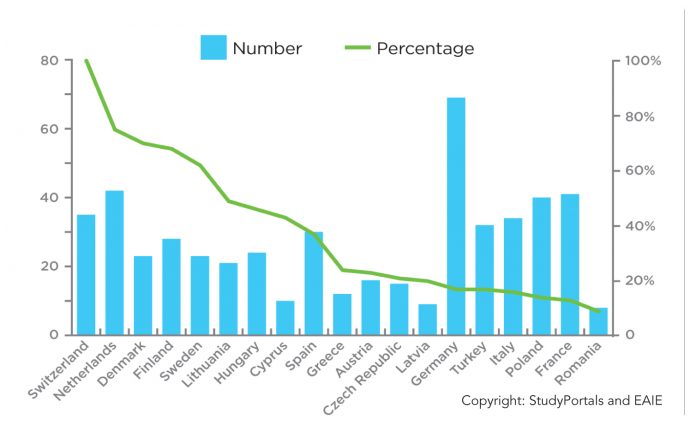

Turkey, for example, offers almost double the number of ETBs than masters. Cyprus and Greece are about even. At the other end of the spectrum there are countries such as Sweden or France, whose English-taught masters offer dwarfs that of ETBs.

Who’s more international?

The Dutch lead the way, matching a high number of ETBs (317) with a high share of their higher education institutions committed to them: about 60 per cent. On average, 38 per cent of higher education institutions in Europe are offering ETBs. This ranges from about 80 per cent in Switzerland to about 9 per cent in Romania.

The top three countries for the relative percentage of ETB offered are Switzerland, the Netherlands and Denmark. At the bottom, we find Poland, France and Romania.

The business of higher education

Business and management is the most popular field of study for English-taught programmes, both undergraduate and postgraduate, followed by social sciences and engineering & technology.

Whereas business and management enjoys an even supply and demand, demand is almost double the offer for ETBs in medicine and health, and the opposite is true for humanities. But recruiting for ETBs can be challenging, the study highlights. This is due primarily to the big differences in secondary education across countries.

And what about the language?

Some institutions, the study reports, have similar English language requirements for both home/EU students and non-EU students. Others are stricter on international students. At the top end, requiring Ielts scores above 6, we find Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark. At the bottom of the ladder, with scores below 5.5, are Latvia, Lithuania and Austria. The latter, though, requires a higher score in the Toefl. The test score requirements are not homogenous across the countries examined.

The challenges ahead

English-taught programmes are a part of the internationalisation strategy. But how do the staff feel about it? The interviewees of the study report that most staff are positive – but some are not convinced, especially at the start of the programme. The most important challenge is staff training: not only in English language, but also in the pedagogy necessary to develop truly international curricula. Most ETBs start out as ‘translations’ of existing programmes, the study reports, and then develop into a distinct programme catering for international students.

Some institutions struggle with these aspects, and this highlights ‘a need for additional training’. The study’s co-author Carmen Neghina said: ‘The starting point is ensuring that teachers and the staff know why international education is so important. English language training is important, but staff also need to be trained to teach international students (See the interview below).

‘Make sure teachers and staff know why international education is so important’

Carmen Neghina, head of intelligence at StudyPortals and co-author of the study, explained the background of the research (above) and told the EL Gazette why it was important to carry it out

What is the rationale behind the study?

International education markets are changing rapidly, especially with the rising numbers of students from Asia and Africa wanting to study abroad because the home offer is not enough to match the demand. Can Europe accommodate all these students? There is a need for clear data – I think this can help us understand what is really happening.

What is the most important finding that the industry needs to keep in mind?

The most striking finding is that the number of English-taught courses is rising fast across Europe. The demand is rising too, so the industry needs to keep up with it. For example there is a rising demand for STEM courses, especially from Asia, that needs to be matched.

There will be a follow-up study delving deeper into the students’ data: where do they come from and what are they looking for? How does demand diversify across all source markets?

What type of training do staff need?

The starting point is ensuring that teachers and the staff know why international education is so important. English language training is important, but staff also need to be trained to teach international students.

Training is important to enable universities to design truly international curricula then?

Yes, especially when the initiative comes from the programme level: then the programme usually starts by translating the curriculum, experimenting for the first year, and moving on. The teachers kind of ‘learn by doing’. Instead, when the initiative comes from management, this usually doesn’t happen – maybe because there are more resources available then.

And… the Brexit question. Have you noticed a drop in the number of students interested in the UK after June 2016?

The number of students looking to study in the UK hasn’t changed. However, what is changing is where students are coming from. For certain European countries the demand is going down, especially for undergraduate degrees, because students are uncertain. Will tuition fees be the same in three years for EU students? For Asian students there is an opportunity, as the Pound is low.